Placidus Houses are Cool, Actually.

Throughout the last half of the 20th century, the astrological community experienced energetic and sometimes aggressive discourse surrounding the topic of systems of house division. These conversations usually sought to prove that such-and-such system of house division was more “accurate”. Though the worst of it appears to be behind us, even many younger astrologers who were not active during the time these conversations were being held express some level of exasperation when the topic comes up today.

Today, the conversations surrounding house division have shifted. It’s less likely to focus on the supposed superiority of one system over another in terms of accuracy. Instead, the dominate conversation focuses more on the accurate historical representation or utilization of various systems. This allows astrologers to clear up misunderstandings or myths regarding various house systems and provides new insight into the adoption of these systems throughout different eras of history and explore what outside forces influenced these changes.

As more ancient forms of astrology become more popular, it is natural that practitioners should migrate to using house systems that are perceived as being older or more original. This has led to the unfortunate side effect of astrologers walking away from the Placidus system of house division. Placidus houses have the mistaken perception of being a more modern form of house division that is mainly utilized for more modern forms of astrology. This is likely due to Placidus being regarded as the default astrological house system where it serves in this default role for several astrological programs due to its popularity in the 20th century. Psychological forms of modern astrology are also regarded as the default or most widely practiced or recognized form of astrology. It’s no wonder, then, why these ideas became associated with the Placidus house system or why students of more ancient forms of astrology would choose to leave it behind, instead choosing house systems perceived as more ancient such as equal and whole sign systems.

The history of the Placidus system is much older than most astrologers believe and touches upon even more ancient ideas of viewing the sky or experiencing time. While we typically trace the origins of Placidus houses to their namesake, the Olivetan monk Placidus de Titis who lived between 1603 to 1668, we can actually see earlier references to Placidus houses in the works of Abraham ibn Ezra who was active in the 12th century. Ibn Ezra describes Placidus houses as a system of house division that matches descriptions in the works of first century astrologer Ptolemy. In his work The Almagest, Ptolemy describes diurnal motion through the utilization of semi-arcs. These same semi-arcs would also be heavily relied upon for calculations of primary directions, a popular timing technique in traditional astrology. However, the roots of the Placidus house system go even deeper than this as their reliance on semi-arcs taps them into the same flow of time as the planetary hours and other Babylonian methods of time keeping.

Semi-Arcs & Primary Directions

Primary directions are a traditional astrological timing technique that seeks to indicate events or qualify periods of time based on the symbolic movement of planets throughout the birth horoscope. They are similar in some ways to secondary progressions, but move the opposite direction as they follow planets based on their primary motion (hence the name primary directions). Primary motion is the east-to-west motion of planets on their daily journey through the sky, most easily recognized in the Sun rising in the east, culminating in the south, and setting in the west. The Sun is not the only planet that performs this motion, as all planets, stars, and degrees of the zodiac will follow these exact steps throughout the course of a day.

The entire path that a planet, star, or degree of the zodiac takes around the earth is referred to as its arc. A semi-arc, then is one part of the arc of any planet, star, or degree. Usually these semi-arcs are divided between the four angles of an astrological chart as each marks an intersection between two great circles that form an easy to observe shift in a planet’s motion and is why these degrees were historically referred to as “pivots”. Planets on the Ascendant make an upward-and-southward pivot, planets on the Midheaven make a downward-and-westward pivot, and so on. So, while a planet’s diurnal or nocturnal arcs (the passage of a planet from its conjunction with the Ascendant until its conjunction with the Descendant or vice versa) can and sometimes are mentioned, we see a much greater focus on the planet’s journey from the Ascendant to the Midheaven, the Midheaven to the Descendant, the Descendant to the Imum Coeli, and from the Imum Coeli to the Ascendant.

The reason why we are discussing semi-arcs is because they are the main focus in primary directions as Ptolemy’s semi-arc method of calculating primary directions became the most widely utilized method throughout the tradition as it solved several technical issues. The most glaring issue is that planets don’t always match up with one another in their diurnal pathing. In the chart in the image below, let’s say we were looking to direct Saturn to the position of the Moon. If you were to look outside you’d see the two planets in a similar relationship, but if you tracked their diurnal motion, Saturn would never come to the exact position of the Moon in the celestial sphere. This is shown in the second image which has the Moon and Saturn in their observable positions, with the glyph of Saturn representing where Saturn will be in the sky when he reaches the same place in his semi-arc as the Moon is in hers at the time of the chart. As you can see, it’s about 12° further north on the celestial sphere.

Semi-arcs become more of the focus in Ptolemy’s method as we come to realize that the exact positions of planets on the celestial sphere cannot be reliably repeated for other planets. Thus, the attention is turned more towards the zodiacal degree of each planet and that degree’s relationship to the position of other degrees. While Saturn in the above image cannot come to the same place as the Moon, their degrees can reach similar positions in order to draw a relationship between them. So when Saturn reaches the same position in his semi-arc as the Moon was in her semi-arc, we see a symbolic connection as Saturn brings something to the Moon that he was unable to carry towards her in the natal chart. This method of focusing on the zodiacal degrees and their connection to the three dimensional positions of planets feels very reminiscent to how connections between planets and fixed stars are measured. Fixed stars are projected to and associated with degrees along the zodiac, and when a planet comes to that same degree they are understood as being “conjunct” that star. Sirius, for instance, is projected to 14° Cancer, so any planet near to 14° Cancer is said to be “conjoined” Sirius, even though Sirius is so far to the south of the ecliptic that no planet will ever come visibly near it.

Signs of Short and Long Ascension

Due to the ecliptic’s angle in relation to the equator, the signs of the zodiac do not rise at the same speed over the eastern horizon. In a perfect world, each of the 12 signs of the zodiac would rise from 0°-29° in two hours of clock time to match with the 24 hours that make up a day. This is not the case, however, as half of the signs of the zodiac will rise in under two hours and the other half of the zodiac will rise in over two hours. This is the phenomenon that is being addressed when we talk about signs as being of “short and long ascension”, sometimes also called “crooked and straight ascension” or even “oblique and upright ascension”. In the northern hemisphere the signs Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius are the signs of long ascension while Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces, Aries, Taurus, and Gemini are the signs of short ascension. This is flipped in the southern hemisphere.

The images above capture this phenomenon best. The first image on the left is set for 0° Libra rising while the second image on the right is set for 0° Aries rising. These two degrees will rise over the Ascendant in the longest amount of time and the shortest amount of time respectively (this is flipped in the southern hemisphere). The difference in the angle of the ecliptic (marked by the orange line) is quite staggering with the 0° Libra ascendant image showing a near 90° angle with the horizon, while the image with 0° Aries rising has the ecliptic at something between a 30°-45° angle to the horizon. These degrees represent the two extremes with other degrees of the zodiac having an angle somewhere between the two pictured. Degrees with angles that are closer to 90° will take longer to rise completely over the horizon, while those with more oblique angles will rise more quickly.

As a result of this angle, another issue emerges. If degrees have unequal rising times over the Ascendant, then they will conclude their journey to the Midheaven at unequal rates. This presents a new challenge when determining when one planet reaches the same position as another. This can be easily observed in an astrological chart. If you are looking at a chart in a “proportional” drawing style, you may notice the varied distance in the angle between the degree on the Ascendant and the degree on the Midheaven. In charts with 0° Aries or 0° Libra rising, the distance between the Ascendant and Midheaven will be an even 90°. This angle becomes the widest when 0° Cancer is on the Ascendant (as the short ascension signs of Pisces, Aries, Taurus, and Gemini can “fill up” the space between the angles) and this angle becomes the most acute when 0° Capricorn is on the Ascendant (as the long ascension signs of Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius “take up” more space). The exact amount of degrees between the Ascendant at Midheaven at these times will vary based on the location the chart is cast from. From the location where this article is being written, a chart with 0° Cancer on the Ascendant has a space of 108° between the Ascendant and the Midheaven (12° Pisces - 0° Cancer) while a chart with 0° Capricorn will have 73° between the Ascendant and Midheaven (17° Libra - 0° Capricorn) as depicted below.

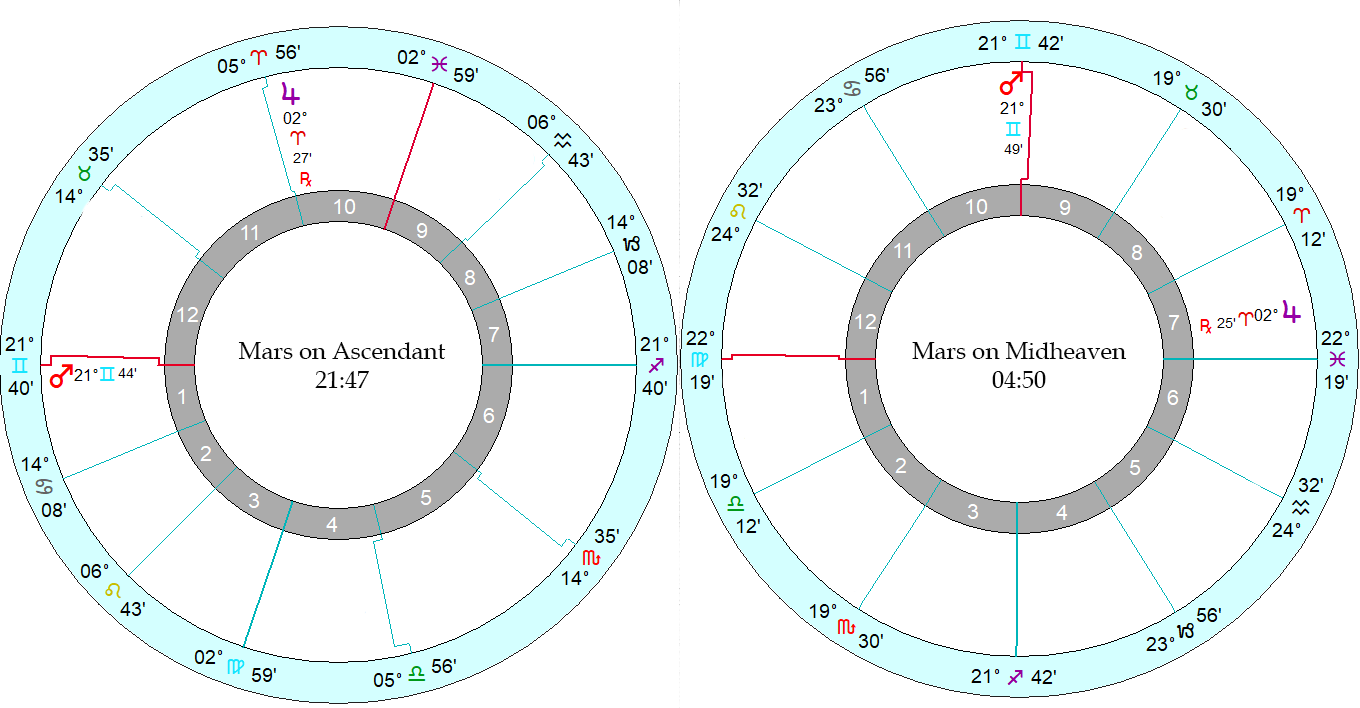

As mentioned above, because of this fluctuation in rising times of signs of short and long ascension, the amount of time it takes for a degree of the zodiac to rise from the Ascendant to the midheaven differs from degree to degree. While opposite degrees of the zodiac will complete their semi-arcs within the same amount of time, degrees that are beside one another will travel more quickly or more slowly than their neighbors. In the example below, Jupiter at 2° Aries will be on the Ascendant at 17:34 and then, later that same day, on the Midheaven at 23:36 meaning it took a total of 302 minutes for Jupiter to complete his semi-arc. Mars at 21° Gemini will be on the Ascendant at 21:47 and later be found on the Midheaven at 04:50 which is a total of 423 minutes. Jupiter completed the same trip from the Ascendant to the Midheaven a full 121 minutes earlier than Mars because the angle the ecliptic made between the Ascendant and the Midheaven was stretched in Mars’s journey (by the signs of long ascension that pushed him up from behind) to make it a more arduous climb.

The reason why we are talking about signs of long and short ascension and semiarcs is because they all come together to offer an alternative to a problem and create the basis for Placidus houses. As we’ve seen, the sky changes and the planets will not exactly interact with one another or cross paths with one another in the way that a 2D astrological chart would suggest. Knowing this, Ptolemy suggested a semiarc ratio system of calculating primary directions and charting a planet’s semiarc through the sky.

Returning to our first example with the Moon and Saturn. As illustrated above, Saturn will not come to the exact position of the Moon in the sky. Their individual diurnal paths and the semiarcs these create are too different. Instead, Ptolemy envisioned the two planets as runners along tracks and sought to compare the rate of travel between two planets while equalizing their distance. Because the angle of the semiarc between the Ascendant and Midheaven (and all other angles, but we’re going to continue to focus on these two) widens or shortens throughout the day, it isn’t fair to exactly compare the journey of the Moon and Saturn. Saturn will have a longer and more angled track to run than the Moon did. The best way to compare their journeys is to discover at what point will Saturn have completed the same percentage of his semiarc as the Moon has hers at the time of the chart.

I don’t intend to get into the mathematics behind this (though it is fairly simple as long as you can cross-multiply) so don’t panic. We are basically only looking to answer two questions. The first, what percentage of the Moon’s journey from the Ascendant to the Midheaven has she completed? The second, when will Saturn complete that same percentage in his journey as the Moon has in hers?

In this chart, the Moon has completed 67% of her journey between the Ascendant and the Midheaven. The semiarc ratio method of primary directions advocated by Ptolemy would seek to discover when Saturn would also complete 67% of his journey (which is currently at 39% completed) and draw a symbolic connection between the two planets standing at similar places along their diurnal paths. It’s as if the Moon dropped something while she was running to the midheaven and Saturn coming to this place is the closest he can get to it to pick it up.

It is this system of determining ratios between the semiarcs of zodiacal degrees that forms the spine of the Placidus house system which makes Placidus a great system to utilize for anyone who finds primary directions to be a core component of their predictive technical work. It’s clear that Ptolemy did not intend for his method of calculating primary directions to be a system of house division (and he did not use it as such), but ibn Ezra, Placidus de Titus, and other astrologers throughout the tradition understood how it could easily be used as one due to its deep connection with the proper rotation of the sky. It is this connection with and sensitivity to the real time ebb and flow of diurnal motion and the widening and shrinking of the distance between the angles of the horoscope that allows Placidus to properly reflect dynamic time with clockwork like precision.

Dynamic Time & Seasonal Hours

As mentioned above, Placidus is unique among house systems in that it reflects a dynamic experience of time. It does this by including the reality that different degrees of the zodiac complete their semi-arcs at different times as a factor in its calcuations. Other time-based systems of house division utilize a static representation of time and how it relates to the motion of zodiacal degrees on their daily journeys around the chart and use that to determine the position of intermediate house cusps (cusps of houses other than the 1st, 10th, 7th, and 4th). Imagine that a planet is a marathon participant and the semiarc is their track with the midheaven serving as the finish line. This marathon track has 2 landmarks (the 12th and 11th house cusp) between the start and finish line that divide it into thirds. Runner performance is recorded when they arrive at the first landmark, the second landmark, and the finish line.

A static time system like Alcabitius houses would simply choose to take the time it took for a planet to complete the track, divide it by three, and say that that result was the time it took for the planet to reach the two landmarks and the finish line. A dynamic time system like Placidus has someone at the landmarks to record the arrival of the planet in real time. A static time system assumes the planet moved at a consistent speed from start to finish while a dynamic time system responds to the planet speeding up or slowing down as it ran the track providing a more accurate and more detailed picture of a planet’s motion.

Because Placidus focuses on the real-time motion of planets and the unique speeds of the degrees they occupy as they move across the sky, when this happens with the Sun, Placidus unlocks the power to tap into the system of seasonal or planetary hours.

Seasonal hours are an ancient system of timekeeping that divided the length of time from sunrise to sunset into 12 equal portions (daylight hours) and the length of time from sunset to sunrise into 12 equal portions (nighttime hours). Unlike our current utilization of hours as 24 equal segments of the day made up of 60 minutes, the length of seasonal hours would vary as daylight increased or decreased throughout the seasons (hence seasonal). During the spring and summer months, the daylight hours will be longer than the nighttime hours, and vice versa during the autumn and winter months. All 24 seasonal hours would be 60 minutes long only on the day of the Vernal and Autumnal Equinox.

Seasonal hours begin from sunrise and are determined by the amount of time it takes for the Sun to complete his diurnal semiarc where he travels from the Ascendant to the Midheaven, and then from the Midheaven to the Descendant. Astrologers are probably more familiar with the seasonal hours as planetary hours, which is a system of qualifying time based on planetary conditions by associating planets with specific days of the week (the Sun and Sunday, the Moon and Monday, etc) and further by specific seasonal hours in that day following a specific pattern where the planet who rules the day also rules the first hour and hands off to the other planets in subsequent hours. Because Placidus houses follows the dynamic, real-time journey of the Sun, accounting for his increasing and decreasing in speed and how that effects the amount of daylight, Placidus has the unique position of being the only house system that accurately reflects planetary hours like a clock face.

Each house in the Placidus system is comprised of two planetary hours. As a result, each house cusp marks the position of the Sun at the beginning of a planetary hour either in the past or the future. With this information, we can know the planetary hour at any given moment simply by knowing how far the Sun has traveled from the Ascendant and what day of the week it is.

The image on the left shows the pattern of the planetary hours for Sunday arranged around the twelve houses of a horoscope. The Sun’s position in the houses will indicate what the planetary hour is with the cusps of the houses and the exact middle of each house representing the transition from one hour to the next.

As the Sun rises over the Ascendant on Sunday, it marks the beginning of the Sun’s hour. When the Sun reaches halfway between the Ascendant and twelfth house cusp, it signals the shift to Venus’s hour as this marks the completion of 1/12th of the Sun’s diurnal arc that day. When the Sun passes the twelfth house cusp, the hour of Mercury begins and so on. This pattern continues around the chart until the Sun reaches the Ascendant again, starting the next planetary day. For a more complete picture of this cycle, please see this Infographic.

The Placidus system’s depiction of two seasonal hours within one astrological house has an interesting overlap with Babylonian methods of time keeping. The Babylonians also reckoned time within the system of seasonal hours which they called simanu. However, it was the combination of two simanu into a unit of time called a beru (double-hour) which formed the backbone of Babylonian time keeping. One beru equaled 1/12th of the Sun’s daily journey and was comprised of 30 units of time called an us which represents the amount of time it takes for the Sun to visibly move one degree across the sky, which is about 4 minutes of clock time. Interestingly, 4 minutes is also about how long it takes a degree of the zodiac to complete its journey across the Midheaven.

Thus we can see the Placidus house system as a depiction of Babylonian time keeping as both focus on the real-time motion of the Sun across the sky as expressed through the seasonal hours and translated to us through the houses of the horoscope. This is expanded by the focus on the us as the Sun steps across the sky degree by degree, forming a natural parallel for the Sun’s motion around the ecliptic throughout the year (also divided into 12 for similar reasons) and his journey around the earth during the year.

Conclusion

The Placidus house system is a fantastic system by which to measure the daily journey of planets around the horoscope. Though it has faced a loss in popularity in recent years due to the association with more modern forms of astrology, it is much older than it tends to get credit for and has roots that go far deeper than its age suggests. This article does not mean to suggest that the Placidus house system was the system of house division employed by Ptolemy in the first century, nor are we trying to argue that this system is Babylonian in origin. The system of houses that we today know as Placidus merely views the sky and the motion of the planets through it in the same way that Ptolemy and the Babylonians did. No other house system captures this view in quite the same way.

Placidus houses became popular in the 17th century due to its ability to accurately reflect the sky as described by Ptolemy. This led to a huge shift in momentum as astrologers began to print and disseminate tables to assist in the calculation of Placidus house cusps, supplanting the previous most popular house system Regiomontanus. This popularity continued into the 20th century where Placidus found its way as the default house system for most astrological tools and software, a position it still (mostly) enjoys today. For a default house system, we could have done much worse than Placidus, a system which provides much more than it gets credit for.