Genii of the Sky

The Fixed Stars in Astrology

This article was originally published as a video on YouTube. You can watch it here!

The stars have long captivated humanity with their motions, dazzling light, and patterns that cultures have used to create vivid and powerful stories that immortalize heroes and deeds. The stars continue to captivate us in the modern age as we explore the edges of our solar system and the limitless black beyond. Astrology, both ancient and contemporary, has a special place for the stars, but they aren’t utilized nearly as often in practice. It’s a little ironic that astrology – which literally means “knowledge of the stars” – focuses way more on the planets than the actual stars themselves. We hear more about Mercury retrograde and Saturn returns than we hear about helical risings or Sirius or anything more obviously stellar and almost no one references stars in natal chart interpretations.

In astrology, a fixed star is any visible celestial body that – basically - is not a planet. So anything we can see in the sky that isn’t the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn is a star. These stars are referred to classically as the “fixed stars” to differentiate them from the planets who each night move further along in their orbits.

The Greeks called the planets “asters planetai” which means “wandering stars” to draw a distinction between those lights in the night sky that moved on their own and those that didn’t. A common misconception is that the fixed stars are called “Fixed” because they were believed to remain stationary. The truth is the fixed stars do, in fact, move but they don’t move independently from one another and remain in their locations relative to one another. Stars actually move in two ways. The first is in diurnal motion much the same ways as the planets. Diurnal motion accounts for the rising and setting of stars and the apparent movement of the celestial sphere as the Earth spins on its axis. The second way that stars move is through precession of the equinoxes.

Precession is a phenomenon caused by the Earth wobbling on its axis which pulls the equinoxes westward causing the backdrop of stars to appear to drift relative to Earth. This is the cause of the differences between the tropical and sidereal zodiacs and why the signs of the tropical zodiac no longer line up roughly to the constellations from which they get their names. Precession was first discovered by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BCE as he took measurements of stellar positions and compared them to older source material. He discovered a consistent difference between his calculations and his sources and concluded that the celestial sphere must be moving at a rate of about 1° every century. Hipparchus’s works no longer survive and we only have access to them through Claudius Ptolemy who performed a similar experiment 260 years after Hipparchus, coming to a similar conclusion.

This precession model wasn’t the only one. We also have the theory of trepidation that sought to describe, explain, and calculate the movement of the fixed stars. Trepidation was the idea that precession wasn’t a constant, one-direction motion, but that the equinoxes would move forward some distance in a specified period of time, before reversing and correcting. The most common ancient explanation was that the stars would move forward about 8° over a course of 640 years before turning back around and covering those 8° again. This theory is something of a self-correcting model and we find it pop up in a few surprising places such as the Picatrix. (Book 2 chapter 4)

Now the fixed stars are fixed in place in relation to one another, so even though they are moving at a rate of 1° every 72 years, they aren’t moving past one another and the constellation patterns aren’t slowly changing. A great way to think of it is like a fabric or wallpaper with a star pattern on it. The whole sheet of fabric can move and it brings the stars along with it, but even though the fabric is drifting westwards, the stars remain in their places in relation to one another. They won’t get closer to one another or further apart.

This is different from the way planetary motion works. The planets each have their own unique secondary motions and speed and this allows them to have different configurations with one another over time. Lunar phase is a good example of this; the reason why we have Moon phases is because the Sun and Moon can have these different configurations with one another in the way the fixed stars can’t with themselves.

Because the Moon is the fastest moving planet it’s easier to demonstrate this with her. (Example, January 13th 2020) Here we see the Moon rising over the eastern horizon near to the fixed star Regulus. Now as a rule, the star Regulus cannot move from this position, but the Moon can. So as we move forward into the next night, we can see the star Regulus is now rising before the Moon does, or to put it another way, the Moon has passed Regulus. That’s the secondary motion of the Moon, or her forward motion through the zodiac as she left the zodiac sign Leo and moved into the sign Virgo.

Moon with Regulus

Moon with Regulus the following night

Each of the planets have their own average speed that they move from the Moon who can move 13° a day if it’s a good day to Saturn who moves about 2 minutes of arc a day, or about 1/30th of a degree. It’s this ability of the planets to cross over the backdrop of the other stars that earned them the title “wanderers” and is why we call them planets today.

Coordinates

In astrology we primarily focus on the zodiac and the ecliptic. The ecliptic is the apparent path of the Sun around the Earth and all of the other planets orbit very near to this line. The ecliptic also contains or demarcates the zodiac itself. Both the tropical and sidereal zodiacs are really just divisions of the ecliptic line into twelve 30° segments that we then refer to as signs. Because the planets move around in this area of the sky, we then say things like “The Sun is in Aries” because the Sun is in that segment of the ecliptic.

Sun on the Ecliptic

Sun on the Ecliptic with Constellations Noted

Sun and Planets on Ecliptic with Signs and Degrees Noted

The planets all follow the ecliptic line very closely but the ecliptic is one specific part of the sky and the stars cover all of the sky. So how do we measure them or give them a position in an astrological chart? How do we know that the star Sirius is at 14° Cancer in the tropical zodiac? It’s actually very simple, we just convert their position into a zodiacal longitude by projecting that star onto the ecliptic.

It sounds complicated, but it isn't unlike a drag and drop methodology. We simply drag the star to the point on the ecliptic it is closest to. For some stars like Spica, Regulus, and Antares it’s fairly simple because they are already very near to the ecliptic to be included within the zodiac band which stretches to 8° either side of the ecliptic so it makes sense to say that they occupy some degree of the zodiac. Other stars – particularly non-zodiacal ones - are much further away so their projection onto the ecliptic comes with different problems. Primarily it’s just the general issues that pop up when you are trying to represent 3D space on a 2D line.

Stars and planets have two positions, they have a ecliptical longitude which measures their positions east or west of the vernal point. In astrological terminology this is the zodiacal position of a planet or star. When we say the Moon is at 10° Aries we’re describing her position as being 10° east of the vernal point and giving her an ecliptical longitude. They also have an eclpitical latitude which is their position north or south or above or below the ecliptic line. Planets never get very far above and below it, but stars obviously are.

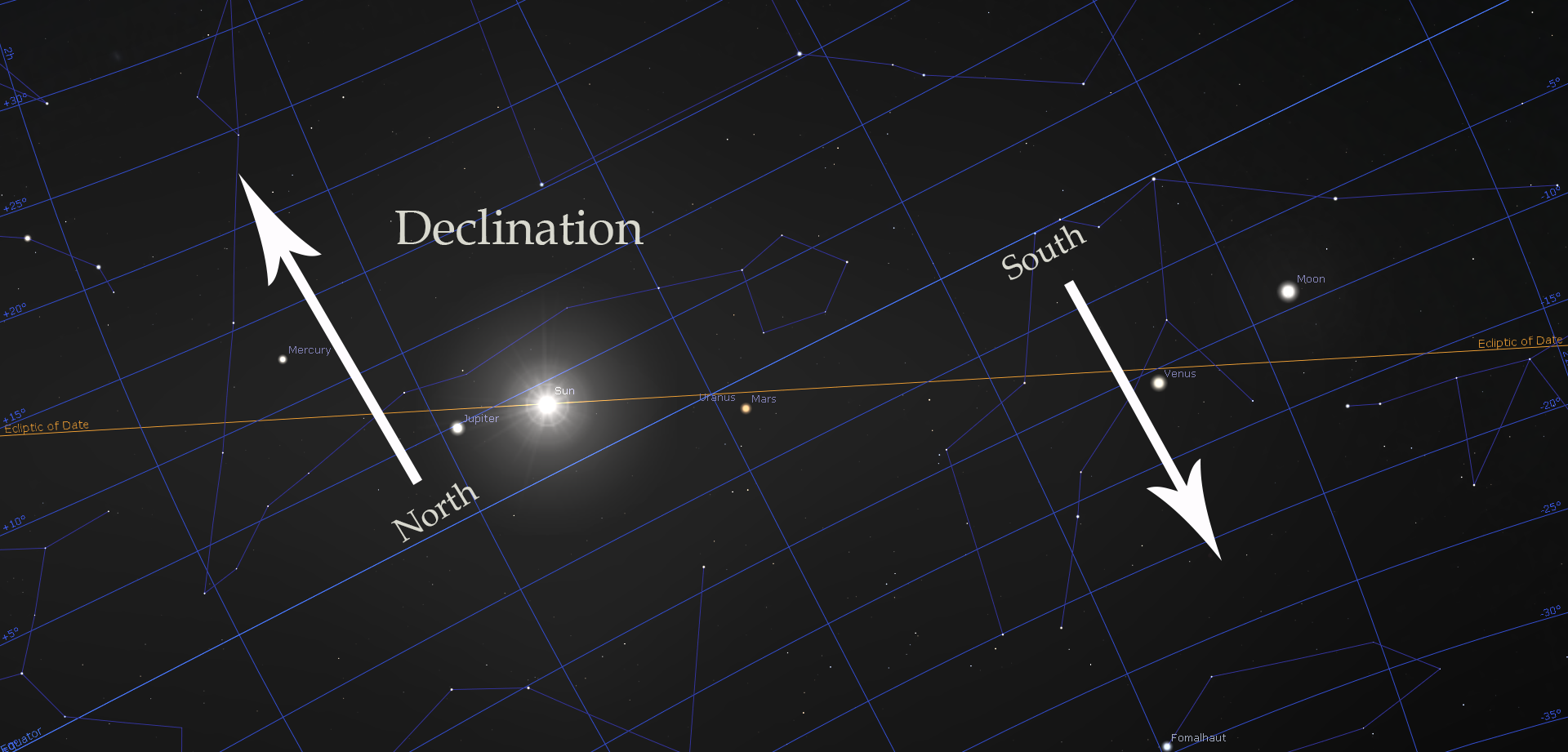

Ecliptic Longitude

Ecliptic Latitude

Ecliptical latitude is not the same as declination. They are similar in that they measure the distance of celestial bodies along a Y-axis, the difference is that declination measures north or south of the celestial equator while ecliptical latitude measures north or south of the ecliptic.

Ecliptic Latitude

Declination

Astrology is primarily concerned with ecliptical longitude. What’s most important is a planet’s position along the zodiac and in some sign. Latitude is mentioned every now and then but definitely plays second fiddle to zodiacal position. This focus is passed on to the stars, we really only care about the zodiacal degree they occupy. This can create some awkward pictures.

Let’s take for example Spica and Arcturus and as another pair Sirius and Canopus. Spica is positioned at 2° south of the ecliptic so is below the line; Arcturus is almost 31° north of the ecliptic, so they are separated by 33° of space north and south. However, when you project the positions of these stars onto the ecliptic they are nearly right on top of each other. Spica is located at 24° 07’ of Libra while Arcturus is at 24° 31’ of Libra. Less than half a degree distant.

The story is much the same for Sirius and Canopus. Sirius is nearly 40° below the ecliptic while Canopus is nearly twice that distance at 75° south. Project them onto the ecliptic and Sirius resides in 14° 21’ of the sign Cancer with Canopus in 15° 14’ of the same sign. Again, a difference of less than a degree counting along the zodiac, but very far apart looking north and south.

One practical difference this makes is the zodiacal degrees won’t necessarily match up with astronomical reality, especially when we’re trying to work with the stars in a chart.

For instance the star Aldebaran is projected to 10° Gemini and I can set an astrological chart for the moment 10° Gemini rises over the Ascendant. However if I set the same time in a planetarium software, the star Aldebaran won’t be found over the horizon. It’s still underneath and won’t be visible at the horizon line until 18 minutes later when 14°57’ of Gemini is on the Ascendant.

This is something to keep in mind when working with fixed stars and be aware that these kinds of things will vary based on a person’s location.

Working With the Stars

Astrologers work with stars in several ways.

The first is that they used primarily to augment the significations of planets or angles. Astrologers don’t normally care about stars that aren’t emphasized some way in a chart. This usually occurs by that star being conjoined a planet or angle. From there, the star’s significations get woven deeply into the area of life represented by that planet or otherwise find themselves expressed specifically through that planet’s powers.

Another way that stars have been used in natal charts is through something called a paran. There do not appear to be historical examples of working with parans and it seems to originate from Bernadette Brady’s work, but the basic idea is that when a person is born with some star on one of the four angles in their chart, we look to see if they have some other planet conjoined any of the angles. Say someone is born with Spica rising, but they also have Mars on the MC. This is a paran and the effects of Mars and Spica are thought to weave themselves into one another in a significant fashion.

Parans are notoriously difficult to work with, however, and many contemporary astrologers prefer to still utilize the projected ecliptical degrees instead of taking the rising and setting of stars in real time. This causes issues where, as we saw with Aldebaran earlier, just because that projected ecliptic degree is rising doesn’t mean that star is following along. Parans are very location specific, so take care when figuring them out.

That Aldebaran example actually includes a paran. Aldebaran’s projected ecliptical degree is 10° Gemini, but for my location, the star doesn’t actually rise until 14° Gemini. When I set the chart for the moment 14° Gemini is on the Ascendant, we can see that the Moon in 16° is currently setting on the Descendant. This is a Moon/Aldebaran paran.

Bernadette Brady in her book of fixed stars advocates taking the entire day to calculate paran relationships between stars and planets and is how online calculators will determine them. This is somewhat controversial among astrologers as it means it will highlight relationships between stars and planets that are not actually occurring during the individual’s birth, but may occur several hours before or after.

Figuring out a methodology of how to work with the fixed stars (either parans or projected degrees) is one hurdle to overcome, but another is just trying to figure out which stars to include in your work and why. If you projected all of the fixed stars onto the ecliptic there would be multiple in every degree, so how do you manage that kind of information?

You have to cull.

Probably the best method of culling fixed stars is letting the chart do it for you. Since fixed stars are only useful when they are conjoined to a planet or angle, just see where those points fall and if there are any significant fixed stars nearby. Keep the orb small; within a degree or two. If you have some then great, if not then that’s okay, too. Obviously the more points in a chart you utilize the more likely you’re going to land on a star, but keeping the traditional seven and then the four angles you’re likely to have one or two close to a fixed star.

Another method of selecting which stars to work with is to utilize historically, traditionally, or culturally significant stars. This criteria can vary from person to person but here are a couple of helpful ways to do this. The first is by selecting only bright, first magnitude stars. Magnitude is a measurement of the brightness of a celestial object, lower numbers are brighter than higher numbers. The Sun’s magnitude is -26.76 while a full moon’s magnitude can be as bright as -12.76.

First magnitude is any designation that is less than 2, so all of the negative numbers up to 1.99 counts. There are 21 first magnitude stars;

Sirius 14° Cancer

Canopus 15° Cancer

Rigel Kentarus 29° Scorpio

Arcturus 24° Libra

Vega 15° Capricorn

Capella 22° Gemini

Rigel 17° Gemini

Procyon 26° Cancer

Achernar 15° Pisces

Betelgeuse 29° Gemini

Agena 24° Scorpio

Altair 2° Aquarius

Acrux 12° Scorpio

Aldebaran 10° Gemini

Spica 24° Libra

Antares 10° Sagittarius

Pollux 23° Gemini

Fomalhaut 4° Pisces

Mimosa 11° Scorpio

Deneb 20° Capricorn

Regulus 0° Virgo

Another culturally important list is the 15 Behenian Fixed Stars. This list is attributed to the mythical Hermes Trismegistus, one of the eight legendary founders of western astrology. We don’t know why these specific stars were selected out of the entirety of the heavenly host, but because they were and the impact works attributed to Hermes Trismegistus have had on the tradition of astrology itself, these are kind of the big deal stars.

The fifteen Behenian stars are:

Algol 24° Taurus

The Pleaides 0° Gemini

Aldebaran 10° Gemini

Capella 22° Gemini

Sirius 14° Cancer

Procyon 26° Cancer

Regulus 0° Virgo

Alkaid 27° Virgo

Spica 24° Libra

Arcturus 24° Libra

Algorab 13° Libra

Alphecca 12° Scorpio

Antares 10° Sagittarius

Vega 15° Capricorn

Deneb Algedi 23° Aquarius

A lot of overlap between this list and the previous list of first magnitude stars since it integrates a lot of bright stars or those that are otherwise culturally significant like the Pleiades. There are some modern renditions of this list that include Polaris in Alkaid’s place so be aware of that. Polaris is not one of the 15 Behenians. This group is very significant within magical practices which is another way stars can be utilized.

Another notable grouping of fixed stars are the Royal Stars of Persia. This is a small group of four significant stars; Aldebaran, Regulus, Antares, and Fomalhaut. In Persian and Zoroastrian cosmology, four stars are named and said to be leaders of the other stars and in charge of rallying them to fight against Ahriman, the destroyer and personification of evil.

In 1771, Anquetil-Dupperon published the first translation of sacred Persian texts into a European language, these texts included our first ever mention of these significant stars. Anquetil-Dupperon identified two of the four as Sirius and the Big Dipper. In 1775, another French astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly published his History of Ancient Astronomy, in this work he makes the claim that the four stars are our familiar Aldebaran, Regulus, Antares, and Fomalhaut in direct contradiction to the works of the translator. This is based on the idea that these four stars were roughly lined up with the solstices and equinoxes around the year 3000BCE.

These identifications remained relatively unchallenged and the stars were called the “royal stars” for the first time by Bailly, a phrase which is absent from the original Persian texts. In a 1945 issue of Popular Astronomy magazine, George Davis Jr. makes a case that the four guardian stars are the constellations of Aquarius and Scorpio, joined by the asterism of the Big Dipper, with the final member being the star Sirius. The Four Royal Stars of Persia is still a very popular topic in contemporary astrology but are beginning to be looked at a bit more skeptically within archeoastronomy.

From a meta perspective, if we were to assume that Bailly’s identification of the Royal Stars is indeed correct, we might expect to see the stars discussed more often throughout the tradition. After all, if they were significant stars to the Persians, we would expect this significance to continue. It is interesting then that Fomalhaut is not included in the Fifteen Behenian Stars nor does it serve as an indicator star to a Lunar Mansion though Aldebaran, Regulus, and Antares are included in both. It may be just a coincidence, but it is suspicious.

Magic of the Stars

While fixed stars are utilized by astrologers to augment the significations of planets or weave in their own stories through the planets and angles, they are also used within magical ritual and talisman making. For this we refer back to our list of the 15 Behenian stars for which Hermes provides us with information on how to use them. In the text attributed to him, Hermes lists images, stones, and plants associated with each of the 15 stars. The basic idea being that we are to combine these things together at astrologically significant times when the stars are emphasized to ensoul a talisman with the spirit of that star.

So for instance, Hermes tells us that the plants fennel and frankincense and the stones crystal and sea snail shells are attributed to the Pleaides, and when we combine them in a ritual with the image of a lamp or a young woman with the proper astrological timing we can create a talismanic object with specific powers. Unfortunately, we only have definitive information on those fifteen stars. Other authors will mention other stars every now and again, for instance Marsilio Ficino mentions Alphertaz, Al-Janah, and Markab and heavily implies that they are stars that Hermes talked about. They aren’t and Ficino also doesn’t provide us with any herbs, stones, or images associated with these three stars like he does for the actual Behenians.

There are two significant moments when a star is emphasized astrologically. The first is when the Moon is conjoined the star. It’s currently very popular to follow Agrippa and the rules he sets out that tell us we make fixed star talismans when the Moon is in a conjunction or applying a sextile or trine to the star. I strongly disagree with this. We can even find this methodology repeated in Marsilio Ficino’s Three Books on Life where he quotes Thabit ibn Qurra as the source of this method. I was not able to independently verify this at this time as the only magical work of Thabit ibn Qurra I’ve been able to obtain is the De Imaginabus which does not include information about fixed star talismans at all. It’s possible that this quote is misattributed or belongs to a work that we have lost or simply not recovered yet. Either way it’s an interesting alternative methodology to working with fixed stars.

The reason why I’m suspicious of this method is because it’s very different from the way fixed stars are handled in the rest of traditional astrology. More typically, fixed stars are not allowed to cast or participate in aspects, they are only effective by conjunction. We see evidence of this all over the place within the tradition. 17th century astrologer William Lilly includes a table to determine planetary strength in his text Christian Astrology and includes conjunctions to Regulus and Spica as positive influences while conjunctions with Algol are negative influences. No other aspect is mentioned.

In Book 3 of Christian Astrology, Lilly provides brief interpretations of the effects of directions, the aspects of all the planets are included, but only conjunctions with fixed stars are covered.

16th Century astrologer Claude Dariot provides a table similar to Lilly’s and most likely was the source of the latter’s, here we see Dariot allows the conjunction with stars of an evil nature to afflict planets while conjunctions with stars of similar natures will improve planets. No mentions of other aspects.

12th century astrologer Guido Bonatti’s Book of Astronomy includes Book 5 which lists 146 aphorisms or considerations. The ninth consideration is a breakdown of the way stars can empower or disempower planets, focused exclusively on how close in a conjunction the planet is to the star without any mention of other aspect types.

There is a very practical reason for this, allowing aspects with fixed stars causes the degrees of influence of these stars to explode exponentially. If you’re using the 15 Behenian stars, then allowing their oppositions, sextiles, squares, and trines will mean working with 120 degrees of the zodiac instead of just 15.

Another important time in a star’s life is its annual helical rise. As the Sun moves around the ecliptic throughout the year, it will cover up different star groups making them invisible for a time. Take for example the fixed star Regulus. It is a star that is the most visible during the winter nights when the Sun is on the opposite side of the sky. As the Sun moves through Spring and into Summer, Regulus will spend less and less time visible each night. Eventually, it will appear one last time immediately after sunset and then it’ll be gone. The Sun will have moved too close to the star and the Sun’s intense light will effectively drown out Regulus’s light. That last evening when the star is visible at sunset is the helical setting and it’s basically the symbolic death of a star.

The Sun Moving Close to Regulus, Rendering it Invisible

Regulus’s Heliacal Set, The Last Time the Star Will Be Visible

The star will spend a period of a few days to a couple of weeks, depending, completely invisible before it will suddenly be seen immediately before sunrise. This moment is its helical rising and celebrated as something of a symbolic rebirth. Helical rises are often used for calendar making purposes. The Pleiades, for instance, are a star cluster associated with rain because their helical rise coincided with the commencement of the rainy season in certain parts of the world. The helical rising of Sirius is another important one, being used to mark the beginning of the Egyptian New Year as it coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile River.

You have to be a bit careful with helical risings because the star’s position north or south of the ecliptic can heavily alter how the helical rising/setting is experienced. The star Algol is projected to 24° Taurus on the ecliptic, but experiences its helical rise around May 8th, when the Sun is around 18° Taurus. So the star visibly rises before the Sun when the Sun is in an earlier degree of the zodiac than the star. For information on how to accurately calculate the heliacal rise date of any star, please see this video.

This moment, this helical rising of a star is filled with significant parallel to the human life cycle and is as close to a birthday or holiday of a star that we can get. It’s also another moment that we can use for magical ritual as pointed out in Austin Coppock’s article A Feast of Starlight in The Celestial Art. While the helical rise date doesn’t necessarily require the same amount of astrological rigor as a more standard electional chart does, it does come with its own unique challenges. The actual date of the helical rise of a star will depend on your location.

When it comes to creating a more standard election to craft a fixed star talisman, we’re really trying to emphasize that degree of the zodiac that we have attributed to that star. While the stars are not perfectly placed along the zodiac and the projection method has its own issues such as stars not visually rising or culminating at the same time their degree does, we’ve symbolically imbued a degree of the zodiac with the power or essence of a star. It doesn’t really matter that the star Aldebaran visibly rises several minutes after 10° Gemini, it’s the 10° of Gemini and its link to Aldebaran that’s most important because at the end of the day, a planet or angle being in 10° Gemini is the closest it’s ever going to get to interacting with Aldebaran since the planets are tethered to the ecliptic while the stars are unbound to the path of the Sun.

So we want the star’s zodiacal degree to be emphasized and we have that happen in a few ways. The first is we want that degree to be on the Ascendant or on the Midheaven. The second is we want the Moon to be applying a conjunction to the star. There’s no set orb for this that is passed down through the tradition, but I try to keep the Moon applying by no more than 5° so that she can be considered angular at the same time. While the Moon is applying the conjunction to the star, you also want her to be applying an aspect to a planet that is of a similar nature to that star.

With all of these astrological conditions met, we have ourselves a fixed star talismanic election. Combining that with the proper materials and prayers and we can produce for ourselves a talisman

Stellar Physis

This concept of stars sharing in planetary nature is old and may have been the first methodology employed to categorically ascribe meaning to the stars themselves. While some stars were culturally significant and worthy of recognition, most of the stars are kind of just background noise. Claudius Ptolemy is the first astrologer we have who uses the natures of one or two planets as short hand to communicate the nature or powers of stars. More accurately he uses it as a way to describe constellations or areas of the sky. In Ptolemy’s system, it’s usually that all of the stars in a constellation are of the same planetary nature, while some more significant stars may stand out as having different natures to their less famous neighbors.

The stars in the constellation Cygnus are said to be of the nature of Venus and Mercury, while Aquila is like Mars and Jupiter. Some of the planetary assignments are themselves a reflection of characterization in myth and religious tales, such as the stars of Andromeda being like Venus while the stars in her mother’s constellation Cassiopeia are like Saturn and Venus. The constellations of the zodiac, perhaps not surprisingly, are given deeper characterization.

Cygnus is of the nature of Venus and Mercury

Aquila is of the nature of Mars and Jupiter

The stars in Aquarius, for example, are described as follows: The stars in the shoulder operate like Saturn and Mercury, those in the left hand and in the face do the same. Those in the thighs have an influence more consonant with that of Mercury, and in a lesser degree Saturn, those in the stream of water have power similar to that of Saturn, and moderately to that of Jupiter.

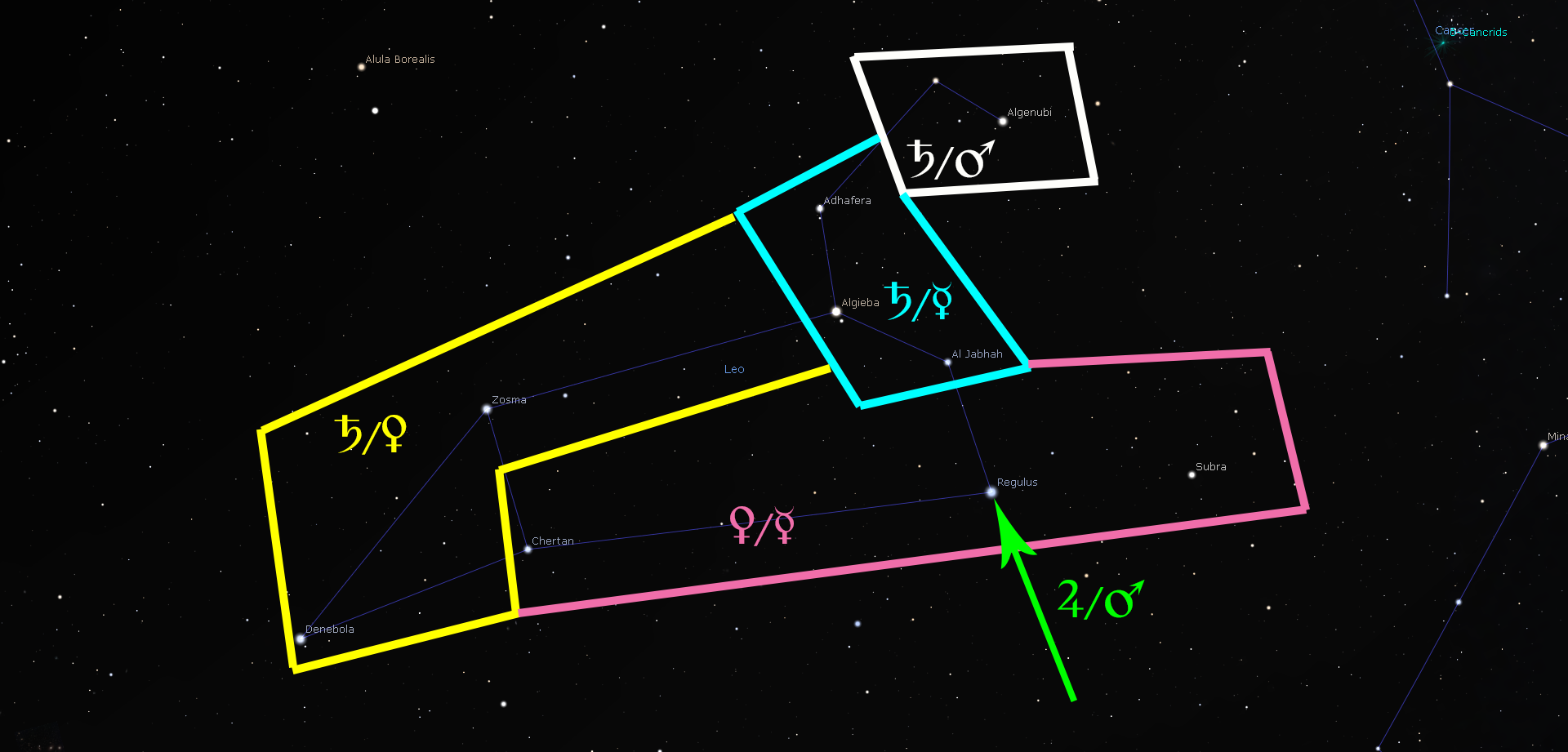

Sometimes individual stars are also pointed out, such as in the case of the Leo constellation where the stars in the head are of the nature of Saturn and Mars, the stars in the neck are like Saturn and Mercury, the hind quarters and tail are of the nature of Saturn and Venus, while the thighs are like Venus and Mercury. Regulus is pointed out as being of the nature of Mars and Jupiter.

The Leo Constellation Divided by Ptolemy’s Planetary Nature

The planetary nature method is a good way to get a broad familiarity with stars that are otherwise not noteworthy and might be the first method employed to characterize most of the stars in the night sky. There are competing associations for some of the stars. While Ptolemy may have been the first astrologer whose work codifies the stars as such, some of his assignments seem strange and later authors would adjust them.

According to Ptolemy, Algol shares the same assignments as the rest of the stars in the Perseus constellation; Saturn and Jupiter. That seems a little strange for a star that has a history of infamy, being associated with decapitation, execution, and the petrifying gaze of the Gorgon Medusa. Later authors adjust the nature of Algol as being like Saturn and Mars; the two malefic planets which is much more thematically appropriate to this particular star.

We have another case of this with the fixed star Spica in Virgo. Ptolemy describes the nature of Spica as being of Venus and Mars which is curious to anyone who had done some work with this star. Later astrologers seemed unconvinced of this assignment, noting Spica’s associations with music and business and argued Spica is of the nature of Venus and Mercury, which seems a better fit.

It seems that early astrologers used the planetary nature of stars to paint them with broad brushes and provide interpretive meeting. The work of Anonymous of 379 provides several great examples of this in action.

“What happens if someone is born at the rising of the bright star that is in Lion’s heart and which lies in the circle of the zodiac at the 20th degree of Leo or at the rising of Arcturus or Arctophilax at the horoscope, the star which rises together with the thirtieth degree of Virgo or at the rising of the bright star of Aquila , which rises together with the seventh degree of Capricorn or if someone is born at the rising of Antares at the horoscope , which lies in the zodiac in the 15th degree of Scorpius (Scorpio); since all the above-mentioned stars have the temperament and nature of Jupiter and of Mars. Therefore, if one of these stars rises at the horoscope or it comes up at the moment of delivery or culminates, it makes people who are born with a disposition of this kind become illustrious generals that subdue regions and cities and peoples, it makes them people who govern, who are inclined to action and act quickly, people who are not submissive and do not accept to be subdued, people who speak frankly, who have a taste for struggle and take pleasure in fighting. They also bring their plans to an end, they are efficient, virile, victorious, they harm their enemies, they are opulent and possibly immensely rich, they are brave and high-souled, they are also ambitious and usually they do not die well. Moreover, in this case people who are keen on hunting as well as experts in and owners of horses and quadrupeds are born.”

Notice that though four unique stars are mentioned – Regulus, Arcturus, Altair, and Antares – they are all said to have similar effects because of their shared nature as Jupiter/Mars combinations.

While the planetary assignments of the stars can give us a broad idea of what a star’s personality is like, we have to look into religious ideas and constellational position to get a better sense of its identity and unfortunately not every star has a lot of detail about its meanings. The stars in the center or heart of a constellation tend to represent the meanings of that constellation more purely or consistently. Regulus is in the heart of the lion and exhibits those Leo/solar significations relating to honors, accomplishments, and health. Antares in the heart of the Scorpion tends to exhibit more honorable warrior characteristics, but still carries the Scorpio/Mars elements of danger.

Stars that are positioned in dangerous parts of the constellations are themselves considered more likely to cause harm like those in the sting and claws of the scorpion, stars in the claws of the crab, stars in the mouths of animals like Sirius, Procyon, and Unukalhai. Stars that make up the weapons of our armed constellations like the sword of Perseus, the club of Orion, and bow of Sagittarius can also symbolize harm. Stars that make up our vehicle constellations can be indicative of travel or sales. You can have a lot of fun with this symbolism.

A huge part of a star is its name, but it is not recommended to dig too much into the meaning of the name to get more information about star associations and manifestations. A lot of the “lesser” stars’ names are just descriptions; Betelgeuse comes from the Arabic for “Armpit of the Giant”. More famous star names can also be disappointing like Aldebaran which means “the follower” because it comes after or follows the Pleiades. Spica also just means “spike”.

While the name maybe less important, the story or religious significance behind the star is clearly valuable. Algol being famously associated with the Medusa myth is a significant part of her character, but it appears that the unfortunate associations behind the star existed prior to its connection with this Greek story. The stars Castor and Pollux also seem to share traits of the twins they are associated with, with Castor being more about mental acuity and Pollux about physical prowess.

This isn’t true for every star and it can be very difficult to explain their meanings. They aren’t as well documented or logically connected as the significations of the planets. Spica is probably associated with wealth because of its connection with harvest, since the star is literally symbolic of a plant, but other connections aren’t quite so clear cut. It’s difficult to explain why Algorab is associated with nightmares other than perhaps because of its association with ravens. For a lot of stars we’re kind of just trusting the advice of those who came before us.

Starlit Path

The fixed stars are a great tool to have in your kit for natal interpretation and powerful allies in ritual work. If you’re interested in exploring this path, check out these recommendations:

Brady’s Book of Fixed Stars by Bernadette Brady

Science and Key of Life by Henry Clay Hodges

Fixed Stars and Constellations by Vivian Robson

Secrets of the Ancient Skies Volumes 1 & 2 by Diana Rosenburg