The Lunar Mansions

Outposts in the Sky

In a previous article we talked about some of the uses and powers associated with the lunar mansions, particularly within a magical context. This will serve as something of a spiritual successor to that article. Speaking less on the powers and uses of the mansions and more about the origins, transitions, and framework of the mansions and how that has shaped or influenced discussion surrounding their utilization.

Scholars are currently divided about the exact origin of the lunar mansions concept. Some think there is evidence to suggest an Indian origin, while others think the origin of the lunar mansions is Chinese. Still, a third opinion holds that the lunar mansions are actually Babylonian in origin and moved east. The Babylonian origin theory is something of a distant third, bolstered mostly by the work of Dr. Ijima Tadao who released a paper in 1930 which detailed his findings and conclusion. Since then, scholars have mostly walked away from his theory as there continues to be no hard evidence of a lunar mansion system in Babylonian materials and some stars which were very significant to Babylonian tradition do not find themselves included in the list of stars associated with mansions.

More contemporarily, people have read a Babylonian or Greek origin or inclusion of the lunar mansions in early Greek and Egyptian material, specifically the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM). Here, proponents usually point to a specific ritual - PGM VII 756-794 - which is simply titled “Prayer”. This prayer is a supplication to the Moon Goddess here named Mene more commonly known as Selene. The supplicant is instructed to call to Selene:

“I call upon you who have all forms and many names, double-horned goddess Mene, whose form no one knows except him who made the entire world. IAO, the one who shaped you into the twenty-eight shapes of the world so that you might complete every figure and distribute breath to every animal and plant, that it might flourish, you who wax from obscurity into light and wane from light into darkness.”

The prayer goes on to list fourteen sounds and 28 shapes or forms, most of which are animals (ox, vulture, bull, etc) but some are not (multiform, virgin, torch, etc). Presumably readers are seeing the number 28 within the context of an obviously lunar ritual and assuming that the 28 are in some way a reference to the lunar mansions leading to the conclusion of the mansions being a part of Greek culture earlier than initially thought and as an argument for an origin in Babylon. However, a more accurate read is probably that this ritual and the number 28 is not about the lunar mansions at all, but a reference to the Days of the Moon.

The Days of the Moon are a sacred timing method which focuses on the Moon’s apparent phases in her synodic cycle with the Sun and are not related to her sidereal cycle which the lunar mansions are predicated on. The time from New Moon to New Moon is 29.5 days, but during that time she is invisible for 36 hours as she comes too close to the Sun to be seen. This means the Moon exhibits 28 different faces or shapes that are observable on different nights as she travels through the sky.

That the Prayer to Mene is a ritual celebration of the lunar synodic cycle makes much more sense than reading it as a reference to her passage through the lunar mansions. The prayer itself mentions the waxing and waning of the Moon. It also only provides 14 sounds perhaps implying they are meant to be made forwards and then repeated backwards to create a total of 28. This would mirror the Moon recreating similar shapes as she waxes and wanes as depicted in the above image (meaning both the 1st and 28th sound is “silence”, reflecting the similar - but mirrored - shape the Moon takes on the 1st and 28th day as pictured above). Finally, that they are referred to as the “28 shapes” would be an unusual way to describe the mansions which are not seen as extensions of or parts of the Moon, but simply areas of the ecliptic where she stays.

Another reference to a potential earlier-than-we-think Greek mention of the mansions occurs in the Latin version of the Picatrix. Translated in Spain in the year 1256, Book 4 of the Picatrix ends with a list of the lunar mansions and their talismanic effects that is attributed to Pliny. This entire section is not present in the Arabic versions which predate the Latin translation by at least 300 years. However, the link to Pliny the Elder would suggest a much earlier Greek source as Pliny died in the first century AD.

Truthfully, it is the Greer/Warnock translation of Picatrix that makes this connection between this list of mansions and Pliny. The newer Attrell/Porreca translation attributes this list to a Plinio and contains an endnote which clarifies the matter.

“This Plinio is not to be mistaken for Pliny, the author of Historia Naturalis. The twenty-eight mansions of the Moon appeared above in 1.4.2-29. In 1.4.1 and 1.4.30, the paragraphs that introduce and conclude the list of mansions of the Moon, the list is credited to ‘Indian Sages’, implying that Plinio is thus an Indian sage. The entire section 4.9.29-56 is an interpolation absent from the Arabic text.”

Further, the Arabic tradition of astrology will often cite Dorotheus when discussing the lunar mansions. This occurs in Al-Rijal’s Book of the Skilled, for example. Dorotheus, of course, being the first century Hellenistic astrologer and author of Carmen Astrologicum. Dorotheus does not directly discusses the lunar mansions in his work, instead it appears that Al-Rijal or some other intermediary has assigned various statements Dorotheus makes about the sign of the Moon in elections to the lunar mansions. For example, Dorotheus states the sign Aries is good for travel, while Al-Rijal says the first and second lunar mansions - both in Aries - are good for travel.

Babylonian astronomy’s first functional zodiac consisted of 17 constellations that fell within the path of the Moon. Weinstock argues that because this zodiac focused on the path of the Moon, it was an early prototype of the eventual lunar mansion system. This would be a much more compelling argument if 17 were anywhere close to the number 28 and if not for the fact that we can trace a clear line of development between this 17 constellation zodiac of the Moon and the eventual 12 sign zodiac focused on the path of the Sun that arose in the 5th century BCE.

Other authors have tried to draw origins for the 28 mansions from the 36 Egyptian Decans. While they may share a focus on stars, the origin of the Decans is decidedly more solar than lunar and focuses on the rising and setting of stars, particularly with their heliacal rise. All in all, we can see fairly weak arguments for a Babylonian, Greek, or Egyptian starting point. Truly, the only compelling evidence of such an origin comes from a single list of mansion names that includes Coptic names of the mansions which match the Arabic titles in many cases. This list must have been composed before the 7th century as Coptic was no longer spoken after this time making the need of such a list moot, but it does little to explain the nearly 400 year long silence on the lunar mansions in the Arabic or Greek tradition following.

This leaves us with an Indian or Chinese starting point. I do not pretend to know enough of the history and development of the lunar mansion systems in either of these cultures to be able to argue which of the two were the originators of the system. We can find ancient texts from both traditions that discuss their respective mansion systems in great detail and that we see the introduction of the mansions to the Arabic world somewhere around the 8th century suggests an eastern origin and westward expansion.

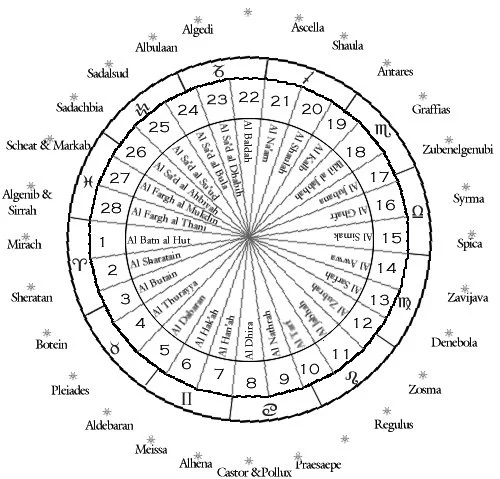

Three Mansion Systems Tour

Having resolved - as much as we’re able to - the question of the origins of the lunar mansions, one question that deserves some exploration is what is the proper framework from which to operate within the mansions? Between the Chinese xiu, Indian nakshatras, and Arabic manzil which is the best system to use?

This is not a great question to ask as it supposes that any one system of lunar mansions is somehow superior to the others. While there is overlap between the mansion systems and how they divide up the Moon’s journey, what becomes obvious when you start to explore them individually and then compare them to one another is that they are simply each a different way to interface with the night’s sky. They are not three systems vying for supremacy with one another, but just three separate lenses to gaze at the stars above.

We can see this immediately when discussing the three systems as several of the main indicator stars and even the starting point differ. The Chinese xiu system begins with the star Spica, while the Arabic and Jyotish systems begin on the other side of the sky with stars in the constellation Aries. This difference in starting point seems like the biggest piece of evidence of a Chinese origin. The lunar mansions would become more connected to the 12 sign zodiac - moving the starting point to coincide with 0° Aries - as it became introduced to cultures who had a longer history with that zodiac. This likely happened when the mansions moved into India and was carried over into the Arabic world who had also had a history with the 12 sign zodiac making it a natural fit.

Below we’ll compare the three mansion systems by exploring the vicinity of the night sky the mansions occupy to show how the Chinese, Indian, and Arabic systems viewed these areas.

As mentioned above, the Chinese xiu system begins with the mansion that corresponds to the star Spica. This is the Horn, representing the horn of the giant Azure Dragon constellation (Chinese astrology divides the ecliptic into four giant constellations which are then subdivided by the mansions). The Indian and Arabic systems both refer to this as mansion number 14, but all three systems see Spica as the main star of the mansion which is not a hard choice as Spica is somewhat alone as a brilliant star among many dim ones in this area of the sky.

For the next lunar mansion, both the Arabic and Chinese systems follow the same pattern. In Chinese this is the Neck asterism and centers on the star Syrma and other stars that make up what we following the Greek tradition would see as Virgo’s legs. The Arabic mansions also focus on the star Syrma as the main star for Al Ghafr, The Covered. In this instance it is the Jyotish tradition that is most unusual. Here, the fifteenth mansion is Svati which is centered on the star Arcturus in the constellation Bootes. A star so far north of the ecliptic that it was unable to be included in the image above. This is a rather stark difference in the Jyotish tradition as generally the mansion indicator stars stick much closer to the ecliptic but there are no circumstances in which the Moon could be observed near to Arcturus.

While the shape is imagined slightly differently, all three mansion systems are back unified again in the next mansion. In Chinese this is Di, the Root or Foundation and is a box-like asterism composed of the stars that we would associate with Libra in the Greek sky tradition. Indian sky lore sees this as Visakha which means “forked” or “having branches”, but is sometimes also called Radha “the gift”. In Arabic, this mansion is Al Zubana, The Claws, a reference to the Giant Celestial Scorpion constellation inherited from Babylon.

There is significant overlap in our next trio of mansions. Though they are differently shaped and may include slightly different stars, the main stars or asterisms are used in all three systems.

The fourth mansion in the Chinese system is Fang, the Room, which is a reference to the belly of the Azure Dragon constellation. It focuses on the stars that we informed by the Greek tradition would known as Acrab, Dschubba, and Fang that make up the face of Scorpio as well as a couple of other attendant stars. Anuradha of the Indian system is also composed of those same three stars and its name - the follower of Radha - is a reference to the alternative name of the 16th nakshatra. Finally, Al Iklil - The Crown - of the Arabic tradition refers to the same three stars, here seen as forming the head or face of the Scorpion.

The next mansions focus on the star Antares. The Chinese xiu and Arabic manzil both call this The Heart in their respective languages. In the Chinese system this is the heart of the Azure Dragon constellation, while in Arabic it is the heart of the Giant Scorpion. In India, this star and mansion are referred to as Jyeshtha, The Elder, in reference to its association with the god Indra.

In a repeat of the above, the Chinese and Arabic systems again refer to the same stars in a very similar manner. Wei (The Tail) and Al Shaula (The Sting) both refer to the elongated and curling tail of their respective constellational figures and are both centered on the stars we following the Greek tradition would see as Scorpio’s tail and stinger. The Indian nakshatras see this as Mula, The Root, and imagined these stars as a long root of a great tree.

The seventh mansion in the Chinese system is Ji, the Winnowing Basket. Here associated both with the classic baskets used to separate grain from chaff, but also became associated with manure and fertilizer baskets due to this asterism’s position under the tail of the Azure Dragon constellation. We see a very similar form take shape in the Jyotish system with Purva Asadha - the First Invincible One - using the same stars and also having the symbol of the winnowing basket (among some others) associated with it. While the Chinese and Jyotish systems break the Sagittarius teapot asterism into two separate mansions, the Arabic system uses it as one larger mansion. The 20th mansion in the Arabic system is An Na’am, the Ostriches, referring to a unique way of viewing the night sky associated with the Bedouin peoples. Here, the stars do not form connect-the-dot style images, but instead represent herds of animals with each individual star representing an individual animal in the herd. An Na’am represents a herd of ostriches going to the river represented by the Milky Way.

With the eighth mansion, Dou, we leave behind the Great Azure Dragon constellation and enter into the realm of the Great Black Tortoise constellation. Dou is the Southern Dipper, a six-star asterism that is not to be confused with the seven-star Big Dipper which held great religious significance. This Dipper is more like the Big Dipper’s little cousin, having significance over wine and offerings to spirits. Of these six stars, the Jyotish system notes two of them as signifying the nakshatra Uttara Asadha - the Second Invincible One - but we lack the symbolic overlap we had between the previous mansions. Finally, the Arabic system’s 21st lunar mansion Al Baldah, The Wasteland, refers to the blank spot between the Sagittarius and Capricorn constellation wherein there are no bright stars to point to. Obviously this mansion is inauspicious because of this.

There is an unusually large amount of space between the eighth and ninth mansion in the Chinese system but we pick back up with Niu, the Ox. This mansion is visually focused on the tail of Capricorn and its main star Deneb Algedi. The Jyotish mansion in this area of the sky is Sravana which is actually focused on the star Altair, the alpha star of the Aquila constellation in the Greek sky tradition. It is not pictured in the above image as Altair resides further north of the ecliptic, so far so that the Moon will never meet it. It might seem strange to focus on a star so far beyond the ecliptic (this would be the second time the Jyotish system has done this so far, the first with Arcturus who is further even than Altair), but the Jyotish system is not alone. While the constellation is itself focused around Deneb Algedi in the Chinese system, there is also an ancient connection between the Niu mansion and the star Altair which refers back to the legend of the Ox Boy and the Weaving Maiden. We’ll talk more about this in the next mansion. In the Arabic system of lunar mansions, the 22nd mansion also focuses on Deneb Algedi. Like how the 20th mansion introduced us to the Ostriches, the 22nd mansion introduces us to the Auspices Complex. This is an area of the sky dominated by 10 pairs of stars who each have a title beginning in S’ad, the Arabic word for lucky, auspicious, or fortunate. Many of these will serve as lunar mansions including this first one, S’ad al-Dhabih, the Auspices of the Slaughterer, representing the good fortune bestowed upon one who successfully completes a sacrifice.

Our next trio of mansions is where things start to get a little interesting and we begin to see more obvious diversity about how the different systems managed the sky. The Jyotish nakshatras get out ahead of the other systems and both the nakshatras and the xiu of China seem to focus their mansions in this section a bit more north of the ecliptic, this is in contrast with the Arabic manzil system which continues to view their mansions as being close enough to the ecliptic where the Moon could be visible among the mansion’s stars.

The tenth mansion in the Chinese system is the Girl asterism, Nu. Anciently, this mansion and the previous mansion Niu were associated with the Ox Boy and Weaving Maiden myth. This myth tells the story of the star-crossed Daughter of Heaven and Son of Earth who meet and fall in love, but must be separated. These two lovers are seen in the stars Altair and Vega, separated on either side of the Milky Way. It is confusing because Vega and some attendant stars do make up their own asterism that is titled Weaving Maiden, explicitly referencing this myth, but the ninth and tenth lunar mansions are also connected to these figures and stars due to drawing of imaginary poles which sort of drag them down closer to the ecliptic. This is interesting because the Jyotish system also has mansions that incorporate Altair and Vega; Shravana and the hidden 28th mansion Abhijit. Unlike the Chinese system which seems to utilize these stars via ecliptic-based proxy asterisms, the Jyotish nakshatra system makes these two stars the nakshatras and doesn’t seem to mind that they are so far removed from the eclpitic. This trend continues with the 23rd mansion in the Jyotish system being Dhanishta, which is focused around the constellation Delphinus which is also quite distant from the ecliptic and so unable to be included in the above image. Finally, the 23rd mansion in the Arabic system is Sa’d Bula, the Auspices of the Swallower. This is another instance of one of the 10 Auspice Pairs being incorporated into the lunar mansion system. Since this pair is made up of one bright star and one dim star, it was imagined that the brighter star was absorbing or swallowing the light of its dimmer partner.

The eleventh mansion of the Chinese system is Xu, The Emptiness. This mansion is made of only two stars that span a fairly empty expanse from the stars of Aquarius to Delphinus. The Arabic mansion system calls its 24th mansion Sa’d al Su’ud after the bright star in Aquarius that it is centered on. This is where the Jyotish system gets a little out of step with the others while Xu and Sa’d al Su’ud incorporate the star Saadalsuud, the Jyotish system jumps over this star completely, instead picking up with its 24th mansion Shatabhisa which is centered on gamma Aquari, but incorporates many of the stars in Aquarius’s water.

Wei, the twelfth mansion in the Chinese system, is the Rooftop, composed of three reddish stars Enif, Sadalmelik, and Biham. It is a sign of danger and often associated with funeral rites as it comes after the Emptiness. The nakshatra system sees its 25th mansion as Purva Bhadrapada, the First Blessed One. It is made from stars associated with the Pegasus constellation in the Greek tradition and carries a similar association with funeral rites like we found in the Chinese Rooftop which is composed of different stars. The Arabic mansion system sees its 25th mansion Sa’d al Akhibiyah as centered on the same star that the Jyotish Shatabhisa was. Here it is viewed as a tent due to its shape and is the only one of the Auspice asterisms to be made of 4 stars instead of 2.

As we reach our halfway point we are again treated to a segment of the sky that contains considerable overlap between the three systems. In the Greek astronomical tradition we would see this area as the Great Square of Pegasus (linking the stars Alphertaz, Scheat, Markab, and Algenib), but all three lunar mansion systems break this square up and use two of its sides as unique asterisms.

In the Chinese mansion system, the 13th lunar mansion is Shi, the Encampment, but also called the House or Pyre. This symbolizes a ceremonial pyre where offerings to the gods are placed and is generally considered a fortunate mansion. Not included in the picture are a small group of asterisms to the south including Thunder and Lightning, perhaps suggesting the pyre is set alight after being struck by lightning. The Arabic mansions see these stars as the Al Fargh al Muqadam, the Front Spout, symbolizing a bucket of water that is pouring out over the earth. This is one of the classical rain stars whose rising introduces the rainy season. The nakshatra Purva Bhadrapada is back after being covered in the previous section because its stars line up exactly with Shi and Al Fargh al Muqadam, but because of the skip the nakshatra system does to have 27 mansions instead of 28 needed to be placed above.

The 14th mansion in the Chinese system is Bi, the Wall. Bi and the preceding mansion Shi were at one time considered one giant mansion, completing the Great Square of Pegasus, but were split at some point into the Encampment/Main Building and its Eastern Wall to give the Great Black Tortoise constellation 7 mansions to match the other Great Constellations. This mansion is indicated by Alphertaz and Algenib and is associated with wealth and construction. The Jyotish nakshatra system of India uses the same two stars to construct Uttara Bhadrapada while the Arabic mansion system uses them to make Al Fargh al Muakhar. This is the other half of the well bucket we saw in Al Fargh al Muqadam, al Muakhar is the first rain star of the year.

Midway through the Chinese system lies Kui, the Legs. This asterism is associated with the hind legs of the Great White Tiger Constellation and represents weapons of war and the arsenal of the emperor perhaps due to the Tiger’s claws. This same figure - with slight adjustments - composed the Arabic mansion Al-Hut, the Fish. This mansion is sometimes misnamed as Batn al Hut, or the Belly of the Fish, but the Belly or Heart of the Fish is actually the red star Mirach. Finally, the Jyotish nakshatra system is the odd-man-out in this instance with its final lunar mansion instead being found centered on Zeta Piscium which is considered the First Point of Aries, or 0° Aries in the sidereal zodiac.

As we make our way around to the halfway point of our journey, we reach the starting points of the Jyotish and Arabic lunar mansions in constellational Aries. We also see considerable overlap between the three mansion systems in this area of the sky.

The 16th mansion in the Chinese system is Lou, the Bond. It is made of the stars Sheratan, Hamal, and Mesarthim and was believed to represent a sickle blade used to reap the harvest. The Chinese system places emphasis on the time of year the Full Moon occurs in the lunar mansions which means we’re seeing more autumnal seasonal symbolism here. This is the first mansion in the Jyotish system, Asvini, which does not include Hamal in its design. The Arabic mansions, on the other hand, exactly mirrors the figure from the Chinese system.

Wei, the 17th mansion in the Chinese system, represents the Stomach of the Great White Tiger Constellation. It represents the storehouse used to shelter the grain or harvest signified in Lou, but also has more general significations of places where things are locked up or stored including repositories, vaults, and prisons. Al Butayn, the Little Belly, is the second mansion in the Arabic system and has a bit of a story to it. There are two sets of stars that different authors use to identify the asterism. The first are delta, epsilion, and ro Arietis which are a dimmer group and closer to the ecliptic. The second are 35, 39, and 41 Arietis which are brighter, further from the ecliptic, but also match with the stars used for both the Chinese Wei and the Jyotish Bharani. This same asterism is regarded as Bharani, The Bearer, in the Jyotish nakshatra system and serves as the second mansion. While both Wei and Butayn represent a stomach, Bharani represents the womb.

The next mansion in all three systems focus on the Pleiades star cluster. While many of us today see the Pleiades as a part of the Taurus constellation, the importance of this cluster to ancient civilizations cannot be overstated and it was seen as its own, separate asterism or constellation to many cultures. The extent of the significance of the Pleaides is far beyond the scope of this article, unfortunately. In the Chinese system the Pleaides marks the 18th mansion, Mao, the Hairy Head, usually seen as the mane of the Tiger. This mansion is usually regarded as unfortunate as it’s associated with trials, the military, and untimely death. The Pleiades mark the third mansion the Jyotish system, known as Krttika, the Cutters, which is associated with the complex god Agni. Finally, the Pleaides mark the third mansion Al Thuraya, the Little Abundant One, which is a central star in the Hands of Thuraya complex. Al Thuraya indicates rain, but also extreme summer heat.

At this point in our journey through the lunar mansions we begin to dip underneath the ecliptic for the first time since the 8th Chinese/20th Jyotish or Arabic mansion. After leaving behind the Pleaides, the all three mansion systems come to arrive at the red star Aldebaran. In the Chinese system, this mansion is Bi, the Net but may have been a trident at some point. This net is used for hunting and this mansion is associated with gathering resources or overpowering others. While the Chinese and Arabic mansion systems see Aldebaran as the main character in a larger asterism, the Jyotish nakshatra assigns Aldebaran as the sole indicator of its 4th nakshatra Rohini. The name Rohini means “the red one” and she is said to be the favorite of the Moon’s wives. The fourth mansion of the Arabic system Al Dabaran means The Follower as it chases after the Pleaides.

The next mansion also seems to be centered around the same star grouping across all three systems. This is a small triangle of stars that appear to be the head or crown of the Orion constellation in the Greek tradition and each of the mansion systems also refer to this mansion as the head of some entity. In China, this is the 20th lunar mansion Zi, the Beak of the Turtle. The Turtle being referenced may be an alternative viewing of the rest of the Orion constellation. This mansion is also notable as being the smallest of the Chinese lunar mansions. The Jyotish nakshatra system calls this asterism its 5th mansion Mrgasira, the deer’s head and the Arabic mansion system sees these stars as its 5th mansion Al Haqa, the Hair Whorl, which itself is a reference to a crown. This mansion is sometimes also called the Head of Jawal.

After a string of agreements between the three systems, we reach a mansion where no one agrees with one another. The Chinese mansion system sees its 21st mansion as Shen, The Three Stars, an obvious reference to the three stars in Orion’s Belt. As with most of the mansions in the Great White Tiger Constellation, this mansion is also unfortunate, signifying executions, decapitation, and violence. The Jyotish nakshatras see their 6th member as Ardra, the Moist One, in reference to the storms that may accompany the rising of this star. While the Arabic system chooses to both spread further out from its previous mansion than the Chinese and Jyotish systems did, but also to stick closer to the ecliptic, instead identifying Alhena and Alzirr (stars in the feet of Gemini) as the indicator stars of its sixth mansion Al Hana.

The 22nd lunar mansion in the Chinese system is Jing, the Well. It is the largest of the Chinese lunar mansions and also serves as the first mansion of the Great Vermillion Bird Constellation. It also incorporates stars from the 6th Arabic mansion Al Hana which the Jyotish system skips entirely. This mansion is very fortunate, having to do with water and cleansing. The 7th mansion in both the Jyotish and Arabic systems focus on the very prominent twin stars Castor and Pollux which are ignored in the Chinese system. In India, this pair of stars marks the nakshatra Punarvasu, The Restorers of Goods which is especially significant as it is said to be the nakshatra the god Rama was born under. The Arabic mansion system sees this mansion as Al Dhira, the Forearm. It is the outstretched paw of the Great Lion Constellation of Arabic starlore which is so massive that it stretches from Castor and Pollux all the way to Spica and Arcturus some 94° away. The remaining 7 mansions will also all be part of the Great Lion.

The nebula in the Cancer constellation is the focus for the next mansion in all three lunar mansion systems. In the Chinse system this is Gui, the Ghost, and represents a carriage or vehicle for the departed and is generally associated with the dead, ghosts, demons, necromancy, but also places where people have died such as battlefields and sites of natural disasters. This mansion is also sometimes referred to as pollen that’s blown off of the neighboring mansion, Liu, the Willow Tree. In the Jyotish nakshatra system, this mansion is Pushya, the Nourisher, having almost entirely opposite associations than it does in the Chinese system. Interestingly, this Pushya does feature a stillbirth in its surrounding mythology (the story of Brihaspati) in which the child is resurrected in the myth. In the Arabic system this mansion is Al Nathra, the Tip of the Nose, and represents the nose of the Great Lion. The verb nathara means “to scatter” or “to disperse” and so the mansion came to represent the sneeze of the Lion.

The 24th mansion in the Chinese mansion system is Liu, the Willow. This mansion depicts the willow’s branches and catkins that blow off into the preceding mansion, Gui. Generally, Liu is an unfortunate mansion that represents tears, sadness, and tragedy in keeping with the weeping willow image. However, this mansion is also associated with divination as there is evidence to suggest that willow stalks were originally used in I Ching divination before yarrow stalks were adopted. In the Jyotish mansion system, this mansion is Aslesha, The Embrace or Clinging Star. This mansion is associated with serpents and snake-imagery and is even made from the stars in the Greek Hydra constellation. While Gui and Aslesha share some of their stars in common, the Arabic mansion system again sticks closer to the ecliptic and borrows stars in the Great Celestial Lion Constellation, the ninth mansion here is Al Tarfah, the Glance of the Lion, an unfortunate mansion generally associated with cursing and casting the evil eye.

Our final stretch of mansions begins with the 25th mansion in the Chinese system named Xing or Niao. We continue our beneath-the-ecliptic dip that we started in the previous mansion and it will not end until we reach back to the first mansion again. This mansion is centered on the star Alfard which was seen as the heart of the Great Vermilion Bird Constellation. The Jyotish and Arabic mansions would focus their attention a bit north from Alphard and center their 10th mansions on Regulus. In the Jyotish tradition this is Magha, The Bountiful, representing royalty and ancestry. In the Arabic tradition this is Al Jabhah which represents the forehead of the Great Celestial Lion.

The 26th mansion in the Chinese tradition is Chang, the Extended Net, which is likely to be a reference to the claws of the Great Vermilion Bird Constellation as this mansion is associated with hunting and trapping. Staying closer to the ecliptic, the Jyotish and Arabic traditions place their 11th lunar mansion with the same pair of stars in the Greek Leo constellation. The Jyotish tradition sees these stars as Purva Phalguni, representing the front legs of a cot or bed. In the Arabic tradition, these stars represent the mane of the Great Celestial Lion.

Mansion 27 in the Chinese tradition is Yi, the Wings, obviously a reference to the wings of the Great Vermilion Bird Constellation. Yi is usually associated with government or religious pronouncements, music, and festivities. Again, the Jyotish and Arabic systems find themselves united with the 12th mansion in both systems centered on the star Denebola. In the Jyotish tradition this mansion is Uttara Phalguni which represents the hind legs of the cot or bed represented in the previous mansion. In the Arabic tradition this is Al Sarfah, the Weather Change as the appearance of this mansion would indicate a shift in the weather from summer to autumn or from winter to spring depending on if the star was rising or setting before sunrise.

The final mansion in our tour is Zhen, the Chariot. This mansion portends wealth and travel, representing carriages which would bring the Emperor tribute from foreign or faraway lands. In the Jyotish tradition, this mansion is Hasta, the Hand. It is notable for suddenly breaking with the Arabic mansion system and rejoining with the Chinese system as both the Jyotish and Chinese system see their lunar mansion among the same stars, but imagined slightly differently. The Arabic mansion system, by contrast, continues to follow along the stars of the Great Celestial Lion Constellation, seeing the 13th mansion among the stars in the haunches of the figure. Al-Awwa, the Howling Dogs, refers to the coldness of the weather at the time of this star’s rising and how it makes dogs howl out in discomfort.

Sidereal? Tropical? Constellational?

The lunar mansions are no strangers to controversy and uncertainty. Not only is there the question of origin, but there are also questions surrounding the practical applications of the lunar mansions. The most glaring of which is the question of measurement. Should astrologers and mages interested in working with the lunar mansions use them within a tropical framework, a sidereal framework, or a constellational framework?

The best answer to this question would probably be to simply add the lunar mansions into the zodiacal framework that you already practice. This provides the most consistency throughout the practice and that consistency is likely more important than any perceived accuracy provided by any particular system as they each have their own issues. While the journey through the mansion systems provided above might create a picture of a system that is inherently constellational, it is arguably not anymore so than the tropical or sidereal zodiacs.

Initially, the Chinese xiu system was measured through an observable, constellational framework where the mansions were unequal in size. Notably, even the Great Constellations are unequal with the Azure Dragon being the smallest. However, even in an early stage of the system, astronomers were looking to create a shorthand system where the lunar mansions became more like a calendar with 28 different named days, one day named after each mansion that the Moon would be understood to lodge within during that day, regardless of which mansion she was observably in at that time.

An image of the unequal divisions of the Chinese lunar mansion system

In the Jyotish tradition, we find the first mention of the nakshatras in the Vedanga Jyotisha text. While we do not appear to find a table that explicitly lists out the positions and length of each of the 27 nakshatras, we do find several references to them being equally divided along the ecliptic and equally divided amongst the seasons. We are also told the Moon takes 1 day and 7 kalaas (a traditional Hindu unit of time corresponding to 144 seconds of clocktime) to cross a nakshatra which can only be possible if the nakshatras are seen as standardized, equal divisions.

Much like the Chinese xiu, if the Jyotish nakshatras were initially conceived as directly observable and unequal astronomical placements, there was a very early push to make them more standardized and equal in the same vein as the signs of the zodiac. This movement to do so appears to have been more successful in India than it was in China as Jyotish astrology appears to have very quickly locked the nakshatras into the sidereal zodiac.

A similar situation appears to have happened with Arabic tradition. The first texts we find that explicitly and verifiably discuss the lunar mansions are the Picatrix and Al Biruni’s Instruction in the Elements in the Art of Astrology. These two texts are somewhat contemporaneous with one another, with the Picatrix likely published in the middle of the 10th century and Al Biruni’s work completed in the beginning of the 11th.

Picatrix clearly lists the boundaries of each of the 28 lunar mansions (cited from unnamed Indian Sages) as beginning with 0° Aries and each mansion containing 12° 51’. Though Al Biruni does not provide such explicit measurements, his introductory description of the lunar mansions is very clear:

“As the zodiac, the course of the Sun in a year, is divided into twelve equal signs, so also the path of the Moon among the fixed stars is divided into daily stations, the mansions of the moon. Of these are 27 according to the Hindus and 28 according to the Arabs. Just as the signs are called after the constellations, so the mansions are called after the fixed stars in which the Moon is stationed for the night. They begin, as in the case of the Sun, at the vernal equinox.”

Al Biruni provides a lot of information about the structure and conceptualization of the lunar mansions in this paragraph by drawing clear parallels between the Sun and his zodiac and the Moon and her mansions. Not only are the mansions equally divided along the ecliptic, but they are called after the fixed stars in the same way the signs are called after the constellations; in name only. This is a clear tropicalization of the lunar mansions that is only made more obvious with the information that they begin with the vernal equinox or 0° Aries in the tropical zodiac.

This continues the theme of the lunar mansions being introduced into a tradition as an observable astronomical event only to quickly be recontextualized and reformatted into the zodiacal structure of that tradition. While the Chinese xiu system ultimately resisted this restructuring and continued as an unequal system, the Jyotish nakshatra and Arabic manzil were seamlessly integrated into the sidereal and tropical zodiacs respectively.

Between the systems it is often the tropical mansion system that gets the most criticism. Due to precession of the equinoxes, the fixed stars and asterisms that the mansions were based on have slowly slipped out of the ecliptical bounds assigned to them. For example, the fourth lunar mansion Al Dabaran is located from 8° Taurus 34’ to 21° Taurus 25’ while the star Aldebaran is currently located at 10° Gemini in the tropical zodiac. Shouldn’t the mansions contain the stars for which they are named?

While it’s clear that the tropical mansion system is the most out of sync with the stars - the stars associated with the mansions are on average located two mansions behind - it is not the only system with obvious errors. It is not uncommon to come across images like the one below which attempts shows the lunar mansions and their indicator stars corrected for a sidereal zodiac and depicted in such a way to suggest they are evenly spaced out and fall neatly within their sidereal boundaries. This is far from the truth.

An image depicting the stars of the Arabic lunar mansions in the sidereal zodiac as equal and evenly spaced. Image also begins with Al Hut as mansion 1, which traditionally is mansion 28.

Between the two images above, the image on the right is designed to accurately represent the positions of the indicator stars in relation to the lunar mansions in the sidereal zodiac. While the majority of the stars do fall within the boundaries of their mansions, one quarter of them do not. This is mostly due to uneven distribution of the indicator stars which the image on the left seems to obfuscate.

The indicator stars of the Jyotish nakshatras fall into a similar pattern. While most of the nakshatra asterisms fit within their boundaries within the sidereal zodiac, about a quarter of them do not. This highlights many of the issues we face when working with the stars. They are messy and attempts to standardize and equalize divisions of space are going to run into problems when the stars themselves simply refuse to be molded into our mathematically minded systems. This is something that tropical astrologers often face from critics who believe that the sidereal zodiac is an accurate representation of stellar reality. Neither zodiac is accurate to the fixed stars and nothing short of a strict constellational framework will get to that level of accuracy. A level of accuracy that was long ago sacrificed in order to maintain order.

While the constellational framework of the lunar mansions is about as popular as a constellational zodiac, we do find references to it in surprising places. Perhaps most surprisingly is in Astrology Restored written by William Ramsey in 1653 where he provides the table to the side.

Astrology Restored covers many topics, but is most well known for its sections regarding electional astrology likely due to the lack of electional content found in the better known contemporary William Lilly’s work. Here, Ramsey discusses the uses of the mansions in elections. Notably, none of the mansions are named in Ramsey’s text and there is no information provided about sources. Very little is said about the mansions at all.

Most strikingly, Ramsey lists the first lunar mansion as beginning in 20° Aries 6’ and says that it is good for journeys and particular kinds of medicine. Without a name to accompany the mansions it is difficult to tell where Ramsey is starting from especially as many of the distances between the mansions do not seem to match up with what we know about the positions of the indicator stars. There also appears to be an error in the text where the 28th mansion reads Aries instead of what must be Pisces.

Regardless, what is clear in Ramsey’s list is that the mansions are unequal by Ramsey’s reckoning and there seems to be an effort to make them consistent with constellational boundaries. Unfortunately it is difficult to tell exactly how he is measuring them or where these divisions came from in the first place and the distances between the mansions do not appear to immediately line up with the distances of the indicator stars. This is a criticism we often find repeated when discussing constellational divisions of the zodiac which are anything but clear themselves.

UPDATE 4/13/2025: I no longer think that this breakdown of William Ramesey’s table of lunar mansions is an accurate representation of his information. See this video for more information.

Conclusion

The lunar mansions are a fascinating lens through which to view the starlore of ancient civilizations. Their creation, transmission, and utilization are often shrouded in uncertainty and what little we do know about them teases us to find out more. Due to this uncertainty, a number of unlikely scenarios and misunderstood judgments have been made about the proper history and application of the lunar mansions, but the reality of the situation is more messy than many would like to give it credit for. It is clear that from a very early stage of the lunar mansion’s adoption there was an attempt to make them more like the signs of the zodiac for ease of use and a general movement away from reliance on the stars and asterisms ancient peoples associated them with. This allowed for an easy access point for those astrological traditions that relied on the sidereal or tropical zodiac.

Even in the early days of the adoption of the lunar mansions into the tropical zodiac, the distance between the stars and their allotted ecliptic boundaries was large and noticeable. While some may see this as an error, it creates a distance and distinction between the lunar mansions and fixed stars that is best respected as the grand majority of lunar mansions do not appear to share similar powers as their indicator stars. There has been some discontent with using the tropical lunar mansion system - even among astrologers who otherwise use a tropical zodiac. However, it’s clear that the sidereal mansion system experiences the same issues on a smaller scale and is not the solution it is often advertised as being.

This conversation about tropical mansions vs sidereal mansions draws an interesting parallel with the decans; 36 stars or asterisms used to keep time in ancient Egypt. The decans have been assimilated seamlessly into the tropical zodiac even though they should have the same problem the lunar mansions do. The decans are likely insulated from any serious conversation along this line as the grand majority of the decan stars are unknown, but these stars should also experience precessional drift and be far outside of the bounds of the decan as provided in the tropical zodiac. However, that is probably a conversation best left for a different time.

Ultimately, the choice for which of the lunar mansion systems to use is best answered by which of the zodiacs you normally use as both experience the exact same issues. Maintaining a sense of consistency is important and it can be maintained both in logic and in practice by syncing up smaller divisions with larger divisions and aligning our view of the sky into one coherent system.